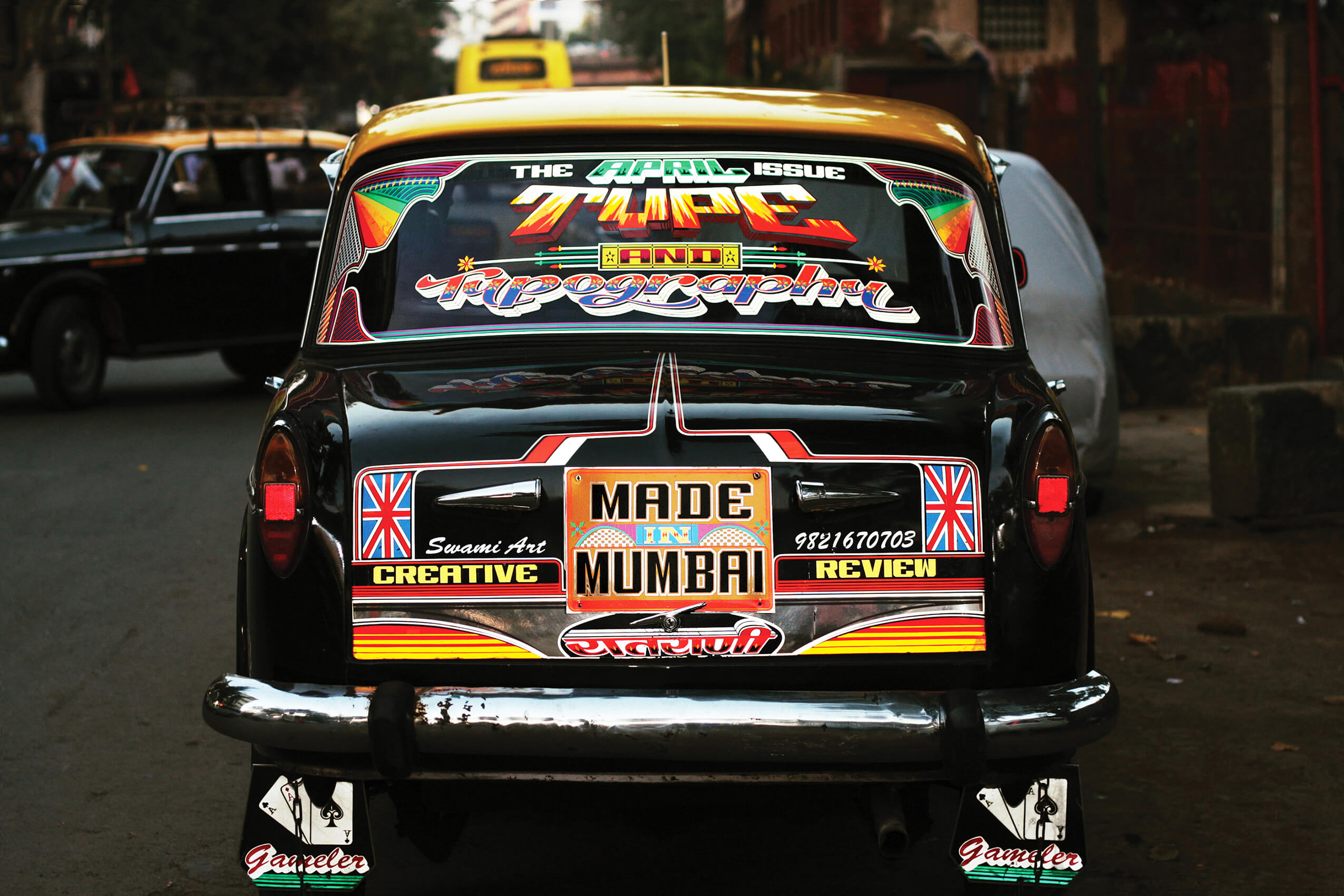

Mumbai Taxi Art

Creative Review commissioned the Mumbai-based design studio Grandmother India to create the cover in 2009. Kurnal Rawat of Grandmother India had already dealt with the city's typographic idiosyncrasies in the past and initiated the typocity project, an online resource for the city's signage. He and his team designed the taxi, and two of the city's leading taxi artists were won over for the manual implementation: Manohar Mistry and his son Sameer.

Father and son Mistry were not only highly sought-after taxi artists, but had brought the artistic stickers to Bombay in the first place. The idea came from an acquaintance who brought photos of illuminated garbage cans from Dubai – and soon, at the Mistrys’ request, the films themselves. They cleverly used these to give the black and yellow taxis a personal, eye-catching touch – a significant competitive advantage among the approximately 65,000 providers.

In an interview at that time, the two stated that the best times for their craft were probably already gone. I wondered what had become of them, and whether they were still giving the taxis that extra soul.

The catch here: there was no address at all.

Bombay has a population of 23 millions.

The search wouldn’t be easy.

Fotos © Creative Review, Aashim Tyagi

Cover Design, spreads by Kurnal Rawat

Ram

Sticker House

The small shop in Girgaon is run by Mangilal Rajpurohit and his son, who immediately offered to help in the search for Sameer Mistry (who now runs the shop alone after the death of his father). A few phone calls later an appointment was fixed, and soon we took a motorbike to Manohar’s workshop.

Sameer Mistry,

artist with a fine blade

Sameer Mistry was evidently pleased with my interest in Typo Taxi and his work in general. He showed me photos of past taxi jobs and a variety of extremely small-scale works, including the artwork for the film JUGAARD, a tribute to Mumbai’s diversity. He had manually hand-cut all of this with a scalpel!

We quickly agreed:

Based on a business card he would create an artwork “Bombay Style” with my logo and the phrase “Tom Koch Graphic Wallah.”

But time was limited, as I had to leave the very next day.

He starts by cutting out the flamed background from countless layers of reflective foil, sticking tongue after tongue to each other. Thus, little by little, the dynamic background is created, which he constantly adds to, adapts and corrects with new pieces of foil. Later, the outlines of the logo are transferred freehand and cut out with a scalpel. 3D effects and shadows are applied, the logo is transferred to a dark background, ornaments and fine lines are worked out. Not once does he hesitate, get stuck or even stick.

All these steps are performed in an incredibly calm, almost contemplative way: cutting, stripping off the remains, touching, pressing down. Over and over again. You can tell the man has been doing this for 17 years.

The next day I pick up the artwork.

It is vibrant, detailed and very Bombay.

The search was definitely worth it.

A Bollywood Lovestory:

Bombay and the Premier Padmini Taxis

The Indian version of the Fiat 1100 had already made its debut on the subcontinent in 1964 under the name Fiat 1100 Delight. Renamed Premier President in 1965, the cars were finally sold from 1974 onwards under the name Premier Padmini – named after the legendary Indian Queen – and took the hearts of the population by storm.

Especially in Bombay they shaped the cityscape, as the city government had preferred the Premier Padmini to other brands such as the Ambassador and had settled the production in the city. This was followed by an indescribable boom.

The Premier Padmini became the car of choice for taxi drivers in Mumbai because it was economical, offered a relatively large luggage space and could be repaired anywhere in small roadside mechanic shops. In its heyday in the 1990s, around 65,000 Kaali-Peeli taxis were registered in the streets of Mumbai. They were stars in Bollywood movies, even popular songs were dedicated to them.

The Padminis had only one disadvantage: they all looked the same.

Taxi drivers therefore began to individualise them, using film stickers on the rear windows to provide information about the location (Bandra) and the districts in which the taxi was licensed to drive. Personal messages (King of the Kings), lateral ornaments and artistically decorated number plates were additionally introduced.

But in 2003 the situation changed: the city administration banned cars that had been registered for more than 20 years from Bombay’s streets for reasons of air pollution. This was clearly aimed at the Padminis, whose production had already been stopped in 2000. From then on their number began to dwindle, and other car brands gradually took over the taxi market.

Today only 50 Padminis are still driving around Mumbai, by the end of 2020 they will have disappeared from the cityscape for good.

With them, a large part of the artistic stickers created by taxi artists like Samir Manohar disappears. Recently, the police have taken action against the stickers because of alleged threats to traffic safety.

The taxi drivers are losing the possibility of individual presentation and the city is losing its rolling icons. Whether taxi artist Sameer Mistry will still be creating his filigree works of art in 10 years is written in the stars.

.

Photos © Wikimedia Commons

Photos © Wikimedia Commons